IT MIGHT BE HARD TO JUSTIFY classing Leo Lionni as a children's author at all. Yes, he wrote and illustrated forty picture books. Yes, four of those books received Caldecott Honors--Inch By Inch (1961), Swimmy (1964), Frederick (1968), and Alexander And The Wind-Up Mouse (1970). And yes, his first picture book, Little Blue, Little Yellow (1959), just celebrated its fiftieth anniversary, having never once fallen out of print. But Lionni didn't compose Little Blue, Little Yellow until he was almost fifty, and by then he had had many solo shows of his paintings in Europe, and was world famous in the advertising and graphic design world--first as an ad man at N. W. Ayer where he worked on campaigns for Ford, Chrysler, and Ladies Home Journal, and then as the artistic director of Fortune. He had also designed the catalog for Edward Steichen's famous 1955 photography exhibition The Family of Man, another book which has never fallen out of print, and had designed the American pavilion at the Brussels World's Fair (Expo 58). This was a man with a full adult career that is almost so overwhelming that every capsule biography (including this one) struggles with what to leave out. So, when children's books were only one small part of such a long and varied career, was Leo Lionni primarily a children's author? As most people know Lionni only as a children's author, the answer would be yes. But as there was art outside of the children's books, there were other books too: criticism, autobiography, and one book length work of fiction.

IN 1959, Lionni decided that he would retire from commercial art at fifty and move to Europe to focus on his painting, and with the success of Little Blue, Little Yellow, he was able to enact that plan. He produced on average a picture book a year and spent the rest of his time on the fine arts. In the early 1970s, after a focused period of portraiture and experimentation with various materials, Lionni set to work on "a 'normal' painting." He relates the endeavor in his autobiography Between Worlds (1997):

IN 1959, Lionni decided that he would retire from commercial art at fifty and move to Europe to focus on his painting, and with the success of Little Blue, Little Yellow, he was able to enact that plan. He produced on average a picture book a year and spent the rest of his time on the fine arts. In the early 1970s, after a focused period of portraiture and experimentation with various materials, Lionni set to work on "a 'normal' painting." He relates the endeavor in his autobiography Between Worlds (1997):"In those first moments the canvas felt frighteningly large...I believe that hands have a memory of their own, for it was in my empty, brushless right hand that the urge to paint was most acutely felt, and despite my loyalty to the human image, I found my mind's eye forming meaningless shapes to fill the empty vertical space. My strong ideological commitment to the human image had always prevented my occasional flirtations with abstract expressionism from affecting this basic believe. So far as I can remember, this was the first time I was seriously tempted to let an imagery develop freely from the inside of the painless process out rather than from a carefully planned scenario."What resulted was a giant orb that, in a flash of inspiration, morphed into an exotic tree that had never before existed. That tree became something of an obsession for Lionni. He began making hundreds and hundreds of sketches of imaginary plants.

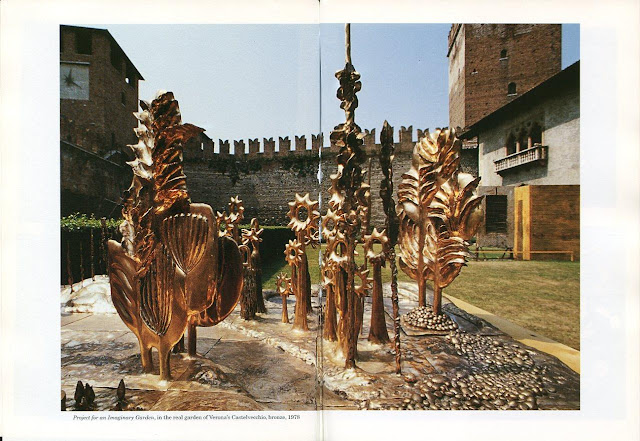

"The drawings were mostly of what from a distance might have looked like ordinary shrubs, flowers, cactus leaves, and branches or parts of these, but at closer range they revealed the telling details of organisms that could have grown only in the soil of the imagination."Many of these sketches became large bronze statues, others became paintings, and a large group of them served as the illustrations for Lionni's only adult work of fiction, Parallel Botany (1977).

But to call Parallel Botany fiction is not quite right. Like Lionni's career, the book defies neat classification. It presents itself as a scholarly dissertation, complete with footnotes and bibliographic support. In fact, it so well mimics that kind of academic writing that it is at times rather dry.

But to call Parallel Botany fiction is not quite right. Like Lionni's career, the book defies neat classification. It presents itself as a scholarly dissertation, complete with footnotes and bibliographic support. In fact, it so well mimics that kind of academic writing that it is at times rather dry."When we think that in 1330 Friar Odorico of Pordenone, with truly angelic devotion, described a plant which gave birth to no less than a lamb, and that as late as the seventeenth century, on the threshold of the first real scientific experiments, Claude Duret also spoke of trees which produced animals, we cannot wonder if the discovery of a botany unconstrained by any known laws of nature has given rise to descriptions that do not always treat the real character of the new plants with objective accuracy."And there's a rather lengthy footnote attached to that sentence too.

Lionni goes on to explain that there exists a whole world of intangible plants, which can be divided into plants that "are directly discernible by us and indirectly by instruments, while those of the second [group]...come into our knowledge only indirectly, through images, words, or other symbolic signs." The history of these plants is comprehensive dating back to prehistoric fossils, with supporting quotes from classical natural philosophers, amateur scientists, archeologists, and many academics. As the characters get more and more ludicrous--the most important prehistoric find, fossil tirils, was made by Jeanne Helene Bigny after consulting a medium at a seance--and the plants get more symbolic--"Uchigaki thinks that the distribution of the tweezers as we see it today is the final result of an intricate series of maneuvers aimed at the conquest of territory, and that these maneuvers bear the most extraordinary resemblance to the moves of the game of Go."--it becomes clear that the whole thing is a joke. A joke told with such a straight face that you might miss it if you aren't paying close attention. He makes it all sound so real.

But under the humor is a very serious philosophical discussion of the artistic process and a defense of its value. Many of the entries on parallel plants contain an in depth history of that plant's discovery--usually by an individual at a moment of inspiration--and the ensuing research--a further extrapolation based on the initial inspiration. This, of course, describes the trajectory that an artist follows in creating a work of art. But Lionni goes further than a simple metaphor. From the introduction in which the fictitious Bodenbach-Kordobsky triangle of name-thing-thing is challenged, "in certain parallel plants the name precedes the physical existence of the plant itself," to the fictional Oskar Halbstein's theory that "the interior of material objects is nothing but a mental image, an idea" and therefore the "interior of parallel plants...eludes even theoretical definition. As we are concerned with a substance that is totally 'other,' that cannot be found in nature, it is literally unthinkable," the question of whether or not thoughts, i.e. moments of inspiration, are real objects is sounded again and again. It is this question that led to the creation of Parallel Botany. From his autobiography:

"The discovery of sculpture...came about because of a total change of vision...The metaphor that had been the sustaining column of all my realities was suddenly unrecognizable: from standing for things, from representing things, the images had become things themselves. The shadows had solidified, the world was no longer about something--it was...Now another "possible" nature, une nature autre, was rising from the other side of the lake."If art is thought and art is real, then thought is real. Enter a new vegetable kingdom.

But is there value in unreal reality? In the epilogue, Lionni gives a non-believer--a traditional botanist--a chance to weigh in. "These gentlemen [the media] have cynically sold us telepathy, alpha-rays, flying saucers, mental deconcentration, acupuncture, the Loch Ness monster, forks bent by willpower and the Black Box." Interestingly, rather than hold up true science as the answer, he goes on to say that fictional plants can't meet our artistic and emotional needs, say, inspire a poem or send a message of love to a beloved.

"But in the fury of his rancor the veteran botanist lumps together the absurd with the possible, madness with reason, good with ill...The sudden questioning of things that have always and in every way conditioned our sensory and mental behavior demands a spirit of invention, an originality of method, a freedom of interpretation normally suffocated by the enormous weight of accepted ideas inherited as a result of our traditional scientific education...It is reported of the Swedish philosopher Erud Kronengaard that he once said to a friend: 'There are two kinds of men, those who are capable of wonder and those who are not. I hope to God that it is the first who will forge our destiny.'"Lionni brought the same message to his children's work in his 1989 book Tillie and the Wall, written just before the fall of the Berlin Wall. In it, two tribes of mice separated by a wall are brought together due to the tenacity of Tillie, a dreamer who imagined "beyond the wall a beautiful, fantastic world inhabited by strange animals and plants."

THE PRIMARY SOURCE for background material for this post comes from Lionni's autobiography Between Worlds. I also drew heavily from the excellent "100 Years of Leo Lionni" maintained by Random House, which includes videos of Lionni on his work, and the linked-from-Wikipedia bios at AIGA and ArtDirectorsClub. TIME magazine's original review for Parallel Botany is available online.

I was very excited to post all of the art from Parallel Botany, and I have done so on my Flickr page here, but just before finishing this post I found that someone has posted the entire book, text and art, if you want to go further than the art without tracking down a physical copy.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

Nice review, the more I studied botany the more I got Lionni's book, with its little jokes about mimicry, evolutionary game theory, urban botany, plant taxonomy etc. It is a complex game he is playing.

ReplyDelete