LANGSTON HUGHES'S SECOND BOOK for the Franklin Watts First Book series was The First Book of Rhythms (1954). Drawing heavily from a course Hughes taught at the Laboratory School in Chicago in 1949, The First Book of Rhythms traces rhythm in all of its forms, from a person's heartbeat to music to oceans and planets to trees and trains and sports. For Hughes, rhythm is all encompassing. Just a few of the chapters titles shows that: "The Rhythms of Nature," "Rhythms of Music," "Rhythms and Words," "Athletics," "Machines," "Rhythms in Daily Life," "Furniture," and in case you somehow missed his point, the final chapter, "This Wonderful World."

The book starts off as an interactive lesson. The child reader is asked to take up a pen or pencil and to try some exercises in written rhythms. "Rhythm comes from movement," Hughes teaches. And each person's movement is distinct, creating its individual rhythm.

There are scientific facts about how sound travels through air or the benefit of streamlined trains and cars, but much of the book reads like a prose poem, a celebration of life in the tradition of Walt Whitman who Hughes quotes in his chapter "Rhythms and Words." A sample of Hughes's prose:

"In growing things there is an endless variety of rhythm from the shaggy, pyramiding pine to the tall bare curve of a towering palm, from the trailing weeping willow to the organ cactus of the desert, from the straight loveliness of bamboo trees in the tropics to the wind-shaped cypress of the California coast, clinging to a rocky cliff near the sea where the waves shower their salty spray."There are the adjectives, the alliteration, and of course the rhythm that would be found in any of Hughes's poems.

If anything, at times Hughes is too lyrical, too abstract, caught up in his song of the world, lists and lists that might benefit from more discussion.

"Knitting creates its own rhythmical patterns by the very way the needles work in wool. So does chain stitching, cross-stitching, or featherstitching in sewing...When mothers curl little girls' hair they simply put the hair into the rhythm of spirals. But curls do not look well on all girls. Each person should arrange her hair to suit the shape of her face..."He seems to have lost his point.

But to Hughes, this was a serious subject. From a lecture the poet gave on teaching poetry: "The rhythms of poetry give continuity and pattern to words, to thoughts, strengthening them, adding the qualities of permanence, and relating the written word to the vast rhythm of life."

He ends the book: "Rhythm is something we share in common, you and I, with all the plants and animals and people in the world, and with the stars and moon and sun, and all the whole vast wonderful universe beyound this wonderful earth which is our home."

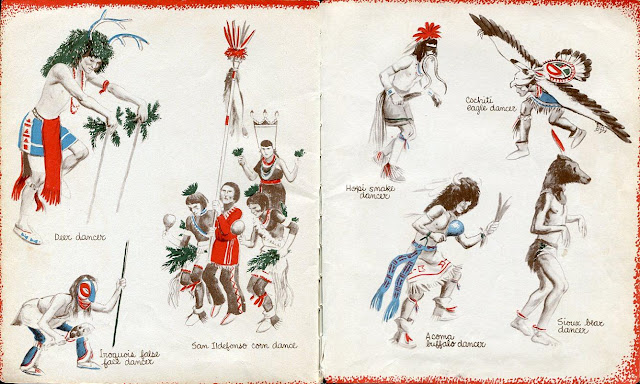

ROBIN KING, the illustrator of the first edition of The First Book of Rhythms, had already had at least two careers before illustrating Hughes's book and had at least two more careers afterwords. The son of an artist (and later television personality), King was rigorously schooled in the arts by his father. When he left high school in the Depression to earn some money, he worked for a newspaper, where he worked his way up to the art department, doing photo touch ups. When World War II broke out and King was turned away by the armed services for health reasons, he drew comic books for both Marvel and DC, which is what led him to children's books. During a radio interview in support of one of his children's books, the program director was taken with King's resonant voice, and King fell into a career as a radio announcer and later the voice over artist in numerous national ad campaigns, such as this one for Mighty Dog dog food.

In 1995, Oxford University Press reissued Hughes's book as The Book of Rhythms with an introduction by Wynton Marsalis, illustrations by Matt Wawiorka (whose farm and blackbird pie appear above), and an afterward by Robert G. O'Meally. All of my background material comes from O'Meally's afterward.

To read the complete The First Book of Rhythms along with all of King's artwork, see my Flickr set here.

See also: The First Book of Negroes

Coming soon: Langston Hughes's The First Book of Jazz

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.