AFTER RECEIVING

RANDALL JARRELL'S TRANSLATIONS for The Brothers Grimm, his editor Michael di Capua suggested that Jarrell try his hand at an original children's story. Intrigued, Jarrell took a notebook to the hammock in his backyard, and with a radio blaring, he composed his own fairy tale,

The Gingerbread Rabbit.

The Gingerbread Rabbit is a variation on the story "The Gingerbread Boy." In Jarrell's version, a young mother makes her daughter a gingerbread rabbit while her daughter is at school. When the mother steps out for a moment, the kitchen implements inform the Gingerbread Rabbit that he is going to be eaten. Frightened by the giant with "dozens of tremendous shining white teeth the size of a grizzly bear's," the Gingerbread Rabbit races out the door with the young mother in pursuit.

In the woods, the Gingerbread Rabbit meets a fox, who tells the rabbit that he is also a rabbit, and invites him into his den with the intention of eating the Gingerbread Rabbit. A real rabbit comes along just in time, and drags the Gingerbread Rabbit away. He brings the Gingerbread Rabbit to his burrow, where he and his wife, who have "always wanted to have a little rabbit of [their] own" adopt the confectionery bunny. The human mother gives up her chase, and decides she will go home and sew her daughter a cloth bunny instead.

AS FANTASTICAL AS THE STORY SOUNDS, and as openly as it wears its folkloric origins,

The Gingerbread Rabbit is built from Jarrell's own childhood, from material he had already mined in his poetry. At the age of eleven, Jarrell's parents separated. His mother returned to Nashville, Tennessee with his brother, while Jarrell remained with his grandparents at their farm in Hollywood. There, his grandparents gave him a pet bunny named Reddy. One traumatic day, the young Jarrell witnessed his grandmother slaughter a chicken. As he describes in his poem "The Lost World:"

[Grand]Mama comes out and takes in the clothes

From the clothesline. She looks with righteous love

At all of us, her spare face half a girl's.

She enters a chicken coop, and the hens shove

And flap and squawk, in fear; the whole flock whirls

Into the farthest corner. She chooses one,

Comes out, and wrings its neck. The body hurls

Itself out--lunging, reeling, it begins to run

Away from Something, to fly away from Something

In great flopping circles. Mama stands like a nun

In the center of the awful, anguished ring.

The thudding and scrambling go on, go on--then they fade,

I open my eyes, it's over...Could such a thing

Happen to anything? It could happen to a rabbit, I'm afraid...

Jarrell asked his grandmother if she could ever do such a thing to his pet rabbit, and his grandmother reassured him that she never would. Then, after a year on his own at his grandparents, it was decided that he should rejoin his mother and brother. Jarrell didn't want to go, and begged his grandparents to let him stay with them. His appeal was denied, and once he had gone back east, Reddy was slaughtered and eaten for dinner.

The Gingerbread Rabbit's fear of being eaten is Jarrell's childhood fear for his pet. And his wish to be adopted by a kind older couple, the real rabbits at the end of the book, is Jarrell's desire to stay with his grandparents. But in the picture book, these fears and wishes could be answered in a way they weren't in reality, with a happy ending.

WHEN JARRELL FINISHED the writing for

The Gingerbread Rabbit, he turned his attention to the illustrations. His wife Mary wrote, "Jarrell rather assumed that the writer found some illustrations he liked, told the editor about it, and the illustrator would come running." After seeing

The Rescuers by Margery Sharp, Jarrell settled on the illustrator Garth Williams without realizing that the illustrator of

Charlotte's Web and

Little House on the Prairie might not be an easy illustrator to hire. In the end, di Capua was able to convince the esteemed artist to take on

The Gingerbread Rabbit.

With Williams in Mexico and Jarrell in North Carolina, all communiques were made through di Capua. In July of 1962, Jarrell sent the following guidelines,

"The rabbit himself ought to be very sincere and naive and ingenuous, so that his whole body and face express what he feels. The big rabbit ought to be handsome, secure and competent-looking; the mother rabbit should be delicate and demure and beautiful. The fox should be very smooth and flashy, like Valnetino playing W. C. Fields. The little girl's mother should be young (28 or so) and beautiful and kind, just the mother a little girl would want; the little girl should be something any little girl can immediately identify with."

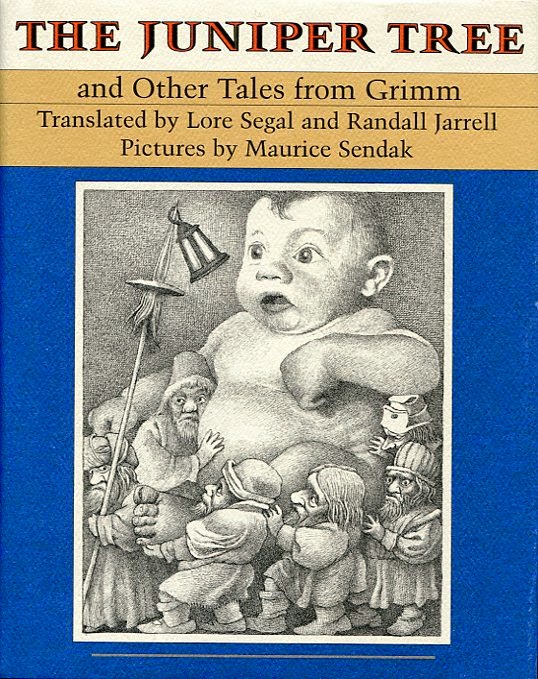

Over the next few months, Jarrell finished writing his second children's book

The Bat Poet, begun in the same hammock that had yielded

The Gingerbread Rabbit. di Capua wanted Maurice Sendak to do the illustrations, and provided Jarrell with examples of Sendak's work. With Sendak's art as a point of comparison, Jarrel began to doubt his original choice of illustrator. In December of 1962, a disheartened Jarrell wrote to di Capua, "If you could tell Williams how much I liked the pen-and-ink style of

The Rescuers, and that I would be enchanted to have

The Gingerbread Rabbit somewhat like that, perhaps he'd feel like it."

Whatever reservations Jarrell harbored that winter, when nearly finished illustrations for

The Gingerbread Rabbit reached him in March of 1963, he wrote:

"I'm delighted with the drawings: the gingerbread rabbit's very cute and touching. The fox is wonderful, and the old rabbit in the colored sketch makes me want to be adopted by him...I believe Williams is getting quite inspired and will make a charming book."

The New York Times agreed. Of the finished product they said, "Garth Williams has drawn his landscape and personae in the best possible way, without "side" or innuendo,

en punto." They said of Jarrell, "As always, [Jarrell's]

prose here is straightforward, the tone is right, the learning informs

subtly, the sensibility is in control. In short, the tale is in perfect

taste."

The book, while now considered the weakest of Jarrell's works for children, resonated with readers as well. It remains in print today, a great accomplishment for a first-time children's book author. Without it, there might not have been the three books to come.

QUOTES FROM JARRELL'S LETTERS come from

The Children's Books of Randall Jarrell by Jerome Griswold with an introduction by Mary Jarrell, and from

Randall Jarrell's Letters, edited by Mary Jarrell. Additional background information came from

Randal Jarrell: A Literary Life by William H. Pritchard.

All images are copyrighted © and owned by their respective holders.

+-+004a.jpg)

+-+005a.jpg)

+-+003a+-+Copy.jpg)

+-+030a+-+Copy.jpg)